There is no economic recession when it comes to courts litigating hotel merchant tax cases between various local tax jurisdictions and the online travel agencies. With an estimated seventy cases at various stages of the process, legal teams representing both sides appear to have guaranteed job security into the foreseeable future.

As municipalities, courts, states, online travel agencies, hotels, lobbyists and lawyers on contingency continue battling, it seems the more they struggle, the deeper they sink

Photo Credit: publicenergy (cc|flickr)

The fundamental issue is whether Online Travel Agencies (OTAs) should be held responsible for collecting hotel occupancy taxes on a) the retail price charged to consumers, or b) on the net wholesale rate paid to the hotel – the current practice. Simply put, the question for juries across the land is if the OTA’s should be paying room tax on markups that are embedded in the quoted room rate.

This topic has been simmering for years, initially with several cases dismissed by courts asking the tax authorities to exhaust administrative remedies. Earlier this year, a couple smaller jurisdictions won victories over the OTAs, but more recently, the tide has turned against the OTAs, with several high profile cases decided in favor of the local municipalities. It is very important to note that the vast majority of these verdicts are under appeal by the OTAs.

Instead of becoming more straightforward as the cases progressively create precedents, verdicts are creating more confusion. New jurisdictions are electing to litigate, while others are choosing to rewrite their tax codes. Smaller markets like Columbus, Georgia have been boycotted by OTAs following court victories, but the same has not held true in larger destinations like Anaheim. A Washington State consumer class action targeted Expedia, adding a new front for the OTAs to defend (Priceline is also currently named in two consumer class actions.) New York City decided to make package booking margins taxable as well. Despite all the activity, there has been no advancement in technical standards or operational process improvements that simplify the identification, recording or remittance of hotel merchant taxes. It seems all parties are in some form of denial regarding the long term impact of changes to the hotel tax environment.

It is likely the hotel merchant tax issue will temporarily become more confusing as appeals processes progress. In several cases, OTAs may see success on appeal, but there is also the potential for further confusion and conflicting rulings based on the number of cases being tried, the rewording of local tax codes, and the broad range of arguments mounted by the plaintiff’s legal teams.

Undoubtedly, individuals taking positions on both sides of this issue will take exception with multiple points raised in the following analysis. In the interest of removing the emotion from the issue and focusing on the facts, each facet of the hotel merchant tax debate will be covered. Ultimately, it appears more uniform taxation and remittance practices must be established to simplify operational processes for OTAs, hotels and the tax authorities. The current chaotic environment is not sustainable and must be addressed cooperatively by the hoteliers, travel sellers and government officials.

Finding America’s Next Top Tax Model

As many are painfully aware, there are fundamentally two business models employed by OTAs when transacting hotels: the first, the Retail Model (sometimes called the commission model) is the traditional method used for decades by retail travel agencies. The OTA only creates a reservation for the hotel, and the hotel charges the guest upon departure. The hotel sets the retail pricing and serves as merchant of record, charging the consumer credit card for the hotel stay. The hotel then subsequently pays the OTA a commission on the room revenue received. The commission level is negotiated between the hotel (or hotel chain) and the OTA.

These retail bookings do not create any hotel room tax issues. The consumer pays the hotel the retail rate, the hotel tax is calculated on that amount and remitted to the tax authority. In some cases on retail bookings, the OTA may elect to charge the consumer a non-refundable service fee at the time of booking. This ensures a revenue stream for the OTA in the event the consumer chooses to cancel the booking prior to arrival. This is a separate charge that is transacted with the OTA as the merchant of record on the consumer credit card transaction. As it is a separate fee and transaction solely for the reservation service, and is not directly associated with renting the room, the service fee is not subject to the hotel occupancy tax.

The Merchant Model is attracting all the attention. The merchant model has also been used for decades – originally by travel wholesalers who combined airline & hotel products into bundled travel packages. Airlines and hotels provided the wholesaler with deeply discounted pricing in exchange for a high volume of business. In some cases, the wholesaler might establish block guarantees and take inventory risk positions (especially at high demand properties or over high demand periods when inventory availability could become problematic) by guaranteeing payment regardless if the rooms were ultimately occupied. Wholesalers also sold hotel inventory on a free-sale basis without liability for unsold rooms, but often with cut-off date constraints that required turning the rooms back to the hotel well in advance of the arrival date if projected block commitments would not be met. These travel packages were priced at the discretion of the wholesaler based on multiple factors.

Merchant model transactions have traditionally seen hotel taxes applied on the net rate paid to the hotel by the wholesalers, not the retail price paid by the consumer. As the hotel was sold in a package, the retail hotel price was impossible to discern. The wholesaler served as the merchant of record for the transaction, providing the consumer with a single invoice for all travel components (and their service fees) bundled into the total package price.

OTAs began leveraging their market power in the late 1990’s and negotiated agreements to start selling wholesale hotel rooms unbundled from other travel components – the practice further expanded after the 9/11 New York City terror attacks. This strategy provided the OTA/wholesaler with unencumbered pricing flexibility that could potentially undercut or dramatically exceed the hotel’s retail pricing structure. The hotel industry, reeling from a loss of control over its retail pricing structure, introduced Best Available Rate (BAR) Guarantees on their brand websites and successfully managed to negotiate terms into OTA standalone hotel rate plans that ensured OTAs could not discount rooms below the hotel’s retail pricing. InterContinental Hotels Group pulling its brands out of Expedia in 2004 served as the bellwether event in restoring OTA-hotel industry equilibrium and allowing the merchant model to work more effectively for hotel suppliers.

A Taxing Challenge

While the merchant model became more palatable to hotels from a marketing and operational viewpoint, OTAs serving as the merchant of record on standalone hotel bookings when the hotels controlled the retail pricing created a perceived tax loophole from the perspective of the local taxman.

The hotel merchant tax issue is illustrated by the following scenario:

- A hotel sets a room rate of $100 as the Best Available Rate (BAR) for a specific date. The rate is sold on the hotel’s website, its brand’s website and on the websites operated by various OTAs.

- Local jurisdictions assess 10% in sales and occupancy taxes on the sale of the hotel room. (Tax inclusive retail price = $110)

- An OTA agency agreement provides a 20% commission on the retail price ($20 commission)

- The hotel room is sold on a standalone basis

- An OTA merchant agreement provides a 20% discount off the retail price ($80 net rate)

Tax Calculation Examples:

A) Direct Retail Transaction (Hotel is merchant of record, no intermediary involved): If paid in advance on the hotel web site, or upon departure from the property, the total amount paid by the guest is $110; $100 room rate + $10 room tax ($100 x 10% = $10 tax).

- Tax Inclusive Retail Price Paid by Consumer: $110.00

- Amount Retained by Hotel: $100.00

- Amount Retained by OTA: $0.00

- Room Taxes Collected: $10.00

B) Commissionable Agency Transaction (Hotel is merchant of record, OTA serves as intermediary): The hotel would collect $110 from the guest and pay the tax jurisdictions $10, pay the OTC $20 ($100 room rate x hypothetical 20% commission) and retain $80 in room revenue.

- Tax Inclusive Retail Price Paid by Consumer: $110.00

- Amount Retained by Hotel: $80.00

- Amount Retained by OTA: $20.00

- Room Taxes Collected: $10.00

C) Merchant Transaction (OTA is merchant of record, OTA serves as intermediary): Due to a tax-inclusive BAR agreement, the total amount paid by a consumer is $110.00. The OTC pays the hotel the $80 room rate + $8 room tax ($80 x 10%) for a total of $88.00. The hotel subsequently pays the tax jurisdictions $8. The remaining $22 is retained as gross margin by the OTC to cover its operating costs and profit.

- Tax Inclusive Retail Price Paid by Consumer: $110.00

- Amount Retained by Hotel: $80.00

- Amount Retained by OTA: $22.00

- Room Taxes Collected: $8.00

The problem is obvious – Even though the guest pays an identical retail price that is established by the hotel under each model, it’s the “extra” $2.00 the OTA nets and the $2.00 less in taxes paid to the local jurisdictions under the merchant model that has fueled the controversy. The apparent ability to access a new tax revenue stream has piqued the interest of politicians seeking every opportunity to cover budget shortfalls.

Life behind BARS

OTA legal counsels argue that selling hotel rooms through the merchant model is the same practice that has taken place for years by all wholesalers. However, a subtle difference exists – Who controls retail pricing?

Before the advent of BAR policies, wholesalers set the price independently from the supplier. This did not present a problem for package bookings because the retail pricing structure of the underlying travel components was protected by the opacity created by the integrated package pricing. When the OTAs started selling hotel rooms on a standalone basis with independent retail pricing flexibility, they suddenly became competitors to, instead of partners with, the hotels. Then, when hotels reestablished control over retail pricing, the merchant business model for standalone hotel bookings fundamentally changed.

Some hotel chains, aware of the OTAs having a structurally reduced tax liability, negotiated tax-inclusive BAR conditions with the OTAs. This eliminated the opportunity for an OTA to match a hotel’s base room rate, but realize a pricing advantage on a total tax-inclusive price basis by passing-through the lower tax amount to the consumer. In the example above, an OTA could hypothetically match a $100.00 base room rate quote, but then sell it for $108.00 (adding their pass-through room tax liability of $8.00) – a hotel would always need to sell that room for $110.00 to cover the full tax burden on the hotel’s retail price. This example structurally produces a 1.82% discount that favors sales through the OTA. Neither the hoteliers or the city tax officials liked that scenario. This is a critically important consideration.

Using the net rate provided by the hotel and an agreement that defines a discount from the BAR (base retail price) as the basis for the calculation, it is impossible to write a mathematical formula to match a tax-inclusive total rate without using the hotel tax rate as a variable. The calculation mandates that the OTA margin on top of the base rate must be multiplied by the hotel tax rate to make the total tax-inclusive merchant model price equal to the total tax-inclusive retail model price. As the tax on the margin (the merchant tax) is based on the hotel’s room occupancy tax rate, the resulting amount is irrefutably a tax derived amount. Counsel representing the locales has logically argued that any amount resulting from a calculation that was based on a tax rate would, in turn, be subject to that tax rate.

This mathematical calculation alone puts the OTA in the unenvious position of choosing between: a) Undercutting the hotel’s tax-inclusive BAR policy – not acceptable to the hotels b) Matching the hotel’s BAR policy – resulting in a potential merchant tax liability, or c) Exceeding the hotel’s BAR policy – making the OTA uncompetitive, reducing sales conversions and increasing traveler claims against the OTA’s best rate guarantee policy. None of the three options is desirable for the OTA; they chose the lesser of the strategic evils: fighting with highly fragmented tax jurisdictions as opposed to the hotel suppliers or undermining their value proposition with travelers.

Making a Bundle

Packaging is fundamentally different from standalone hotel sales transactions and as a result, requires different treatment for hotel occupancy tax. Wholesalers set the package price independently from the price assessed by the hotel. Package pricing is based on many factors including, but not limited to, the discount provided by the travel suppliers, the relative cost ratio between the travel components, the suppliers’ retail pricing, competitive package pricing, and most importantly, market demand.

OTA legal counsel are appearing to generalize all hotel sales as a common process – apparently in an effort to link standalone merchant model hotel sales with traditional wholesale package transactions. This approach seems to be backfiring.

New York City recently rewrote its hotel occupancy tax law to incorporate package bookings. This is not only bad for the OTAs, but it also creates a new tax liability for all traditional travel wholesalers and tour operators. This is a horrible idea – not because it increases travel seller tax liability, but because it is technically impossible to accurately assess a tax based on margins for an individual travel component within a package.

Skeptical? Evaluate this example itinerary – it reflects actual pricing and costs captured in 2009.

Standalone Retail Pricing:

- Airline – Chicago O’Hare to Dallas/Fort Worth Non-stop Roundtrip $1,082.00

- Hotel – 2 Nights 3-star Property $445.05

- Car Rental – 3 Days Compact Car $293.00

- Total A la Carte Price: $1,820.05

Package Pricing (Identical Travel Components & Dates):

- Total Package Price $954.96

- Package Savings: $865.09

- Package Discount: 47.5%

Travel Package Component Pricing Breakdown:

- Airline Cost – $378.70 (65% discount of $703.30)

- Hotel – Hotel Base Rate $251.55 (35% discount of $193.50) + 15% Hotel Tax ($37.73) = $289.28 Hotel Total

- Car Rental -$219.75 (25% discount of $73.25)

- Total Travel Component Cost $887.73

- Package Markup $67.23 (7.6% markup)

- Total Package Price: $954.96

The most equitable approach to calculating hotel taxes in a package is to use the traditional methodology and base the calculation on the net rate charged by the hotel.

For taxation authorities, the temptation may exist to follow the lead of New York and attempt to mirror the standalone hotel taxation process to assess a hotel merchant tax on the sellers markup. There are two potential methods to accomplish such a result a) directly tax the margin of the wholesaler, or b) require full transparency of package component pricing. Unfortunately, neither of these methods is viable.

Basing hotel merchant taxes on the markup does not adequately isolate the hotel component. In the scenario above where the total package price is less than the standalone airfare, it is impossible to accurately define a hotel retail price.

A similar process is employed by New York City's hotel merchant tax calculation on a travel package bookings transacted by Online Travel Companies

One could attempt the convoluted process of calculating the “additional rent” as dictated in the updated New York City tax law by 1) taking the ratio of the wholesale hotel price to the total cost of the travel components, 2) multiplying the result by the package markup, and 3) extracting the tax rate to arrive at the hotel merchant tax: ($251.55 / $887.73) * $67.23 = $19.05. At the standard 15% merchant tax rate, the hotel tax allocation would be $2.86. While this calculation conceptually incorporates the markup into the taxable basis, there are two major problems with this approach:

- The calculated hotel tax has minimal direct relationship to the actual price charged by the hotel or and the ability of the reseller to generate margin (which is significantly based on the level of discounts provided by the suppliers

- The amount of hotel tax payable would constantly fluctuate depending on the ratio of the hotel component to the other travel products and wholesale markup

What if the hotel offered no discount (only a retail price) to the travel wholesaler? While one could say this is typically unlikely for hotels, this practice is very common for air components in travel packages. If the hotel component was included at the full retail price, with the difference passed on to the consumer at cost, the total package price would have been $1,148.46 (still reflecting a 36.9% discount from the individual component prices. The new calculation would be ($445.05 / ($887.73 + $193.50)) * $67.23 = $27.67 * 15% = $4.15 As a result, the hotel merchant tax would be increased by 45.1%, despite the fact that the hotel offered no discount to the wholesaler. This is clearly asinine; and that may be a gross understatement. The tax authority is applying levies against amounts where they have no reasonable claim.

More ludicrously, the New York City has also created an highly creative formula for wholesalers to apply to package components that are procured from another intermediary and the underlying component cost is not known. The law requires “a 15% markup on 70% of the average retail rate of a similar room may be used to compute additional rent.” For the example above, let’s use $445.05 as the retail price for a comparable hotel room. The calculation is $445.05 * 70% * 15% = $46.73 (the “additional rent”) * 15% (the hotel merchant tax) = $7.01. That creates an incredible 145.1% increase in the merchant hotel tax liability than the original calculation. Too bad there was no discount offered by the hotel that would enable a higher package margin for the distributor.

Exactly who keeps track of comparable retail pricing on a daily basis by room category was not defined. Does the jurisdiction track this data? Does the wholesaler track this data? Do the hotels track this data? What if other jurisdictions decide to use an arbitrary tax basis that differs from the New York City approach, do those data points and calculations also need to be tracked and calculated by the wholesaler?

If there are multiple resellers involved, each is responsible for paying their own respective markup on the hotel portion of the package. Does this require that the first wholesaler must provide open communication and disclosure of its base hotel price and markup to the second wholesaler? That will not be a popular activity and would violate merchant agreements with the hotel companies that require wholesaler pricing confidentiality.

So given the three scenarios outlined above, the hotel merchant tax payable on the package including the Dallas hotel (using the New York City calculation methods) could be $2.86, $4.15 or $7.01. Ironically, if a supplier of another travel component provides a lower price, or a greater discount, the higher merchant tax liability for the hotel, regardless of the discount it is offering. This represents a highly regressive tax for the hotelier.

If the New York City merchant hotel package tax calculation was not so sadly off base and already law, the approach could be considered laughable. I fully expect that the updated New York City tax law pertaining to packages will not be successfully defended by the city in court.

Applying hotel taxes to a wholesaler’s package markup does not work due to the presence of multiple travel components. It is impossible to associate the markup with a single component in a multi-component package. In the scenario above, it could be argued that the seller’s $67.23 markup was primarily driven by an ability to secure a $703.30 discount on the air pricing, not the combined $229.02 discounts from the car and hotel components. Some revenue managers might criticize the travel seller for allowing so much potential margin to be translated into consumer benefit, but this was not the case. The travel supplier in this scenario arrived at the margin indirectly by intentionally setting the total package price $5 below an identical package on Orbitz. Package margins are highly variable, providing unpredictable tax revenue streams and demanding exhaustive audit resources (including verification of other package component prices) by both tax authorities and travel packagers.

The second alternative, requiring component price transparency does not work either. Requiring full disclosure of underlying component costs and travel seller markups to consumers could be potentially catastrophic. Consumer pricing would undoubtedly increase as travel suppliers lose a valuable outlet for discounting distressed inventory. Traditional wholesalers, especially those holding equity positions in travel suppliers would be extremely hesitant to reveal pricing strategies for distressed inventory to competitors. Travel packaging continues to provide exceptional values for consumers and remains a highly effective method for travel suppliers to protect retail pricing structures while offering price opacity for discounts on distressed inventory.

Total package prices are not often less than the cost of a single travel component, but I have personally booked three different trips over the past year where the combined Air / Hotel / Car package price was less than the standalone roundtrip airfare. Requiring travel resellers to provide component and markup price transparency would cause suppliers to withhold these deals from wholesale distribution.

My recommendation to every OTA legal counsel would be to start differentiating package sales from standalone hotel sales. Maintaining the argument that both methods should not be subject to hotel merchant tax may superficially look like a good courtroom tactic, but the point is only mathematically accurate for packages. In the long term, the most defensible position is to keep the package sales free from occupancy taxes, rather than have packages blanketed under the same hotel merchant tax liability as standalone hotel sales.

Hot Potato

The level of frustration regarding the hotel merchant tax issue is so high, I once heard a major travel seller’s CFO suggest that the hotel merchant tax should be calculated, and simply passed through to the hotel for remittance to the appropriate tax authorities. One does not frequently hear rational CFO’s volunteering amounts currently booked as retained earnings reclassified as accounts payable.

The CFO’s frustration level with the merchant tax issues motivated him to consider making the merchant tax someone else’s problem. Unfortunately, even collecting and giving the money away was not an option for the following reasons:

- There is no automated method to communicate the merchant tax amount to the hotel. The database schemas and messaging standards required to support interfaces do not exist. As a result, the hotel could not be advised how much was allocated by the distributor for the merchant tax.

- Most OTAs use a single-use ghost credit card number to transact the payment with the hotel. As the hotel triggers the payment using standard credit card processing, collecting the additional merchant tax amount would require substantial non-standard training processes to accurately account for new revenue and expense .

- If the hotel did request the additional amount and receive it from the travel seller, they could not include the amount in their normal tax remittance process – the additional amount would be reflected as an overpayment of occupancy tax as the liability would technically be for revenues earned by the travel seller.

- If using new offline processes, a hotel collecting the merchant tax amount and crediting the property management system would put the hotel out of balance by having collections exceed the revenue percentage basis for tax payments.

- Due to the lack of coordinated and standardized processes, any merchant tax amounts held by the travel seller or hotel waiting for remittance are placed into a suspense account. If processes create payment/collection inconsistencies, the resulting differences become “tax breakage” which is a highly undesirable scenario inviting potential litigation when taxes collected exceed the taxes paid.

Having never been implicated in a hotel merchant tax suit, the travel seller was very interested in keeping its record intact. Realizing that they were unable to communicate efficiently with the hoteliers or the tax authorities, the organization made the conservative decision to forgo transacting standalone hotel bookings under the merchant model until the litigation environment was more clearly defined – they are still waiting.

Multiple Tax Personality Disorder

As the previous section illustrated, merchant tax payments from the travel seller to the hotel are highly problematic. The only more problematic process would be remitting payments from the travel seller directly to the tax authorities. The root cause of this issue is that travel sellers rarely receive detailed tax allocations from the hotels. In the case of a New York City hotel, the distributor might know that the correct tax rate is 14.75% of the room rate, plus $3.50 per night. Unfortunately, the underlying taxes may need to be remitted to multiple entities. Some tax detail may be provided – for example, New York City Hotel Taxes are outlined below:

- New York State Sales Tax: 8.875%

- New York City Sales Tax: 5.875%

- New York City Occupancy Tax: $2.00 per day

- New York City Hotel Unit Fee: $1.50 per day

OTAs would not generally know if these taxes are paid to one or more jurisdictions – OTAs never see detail regarding what tax liabilities are due to which jurisdictions.

Recently, 173 Texas municipalities including San Antonio won a $20.6 million class action verdict against the online travel companies, but that suit did not apply to the County & State tax assessed on the same hotel stays. For example, San Antonio collects 9.0% tax on each occupied hotel room. However, the Texas state hotel tax rate is 6% and Bexar County assess an additional 1.75% tax on room sales. As those jurisdictions were not a party to the San Antonio class action. So while a consumer pays 16.75% tax on a San Antonio hotel stay, only 9% is currently subject to the hotel merchant tax.

The travel seller also has no formal method to know which jurisdictions have tax laws that require the payment of hotel merchant taxes. If the traveler in the above example spent a night in Houston, the largest city in Texas, there would be no merchant tax liability as the Houston did not participate in the class action suit. Understanding exactly how much is owed to whom, based on what exact calculation, within a specific time frame, is fundamental for a tax process to operate efficiently for all involved. Independent of litigation currently underway, OTAs do not know past, present, or potential future tax liabilities associated with hotel merchant taxes.

Remote Control

A critical determining factor in each hotel merchant tax case is the exact terminology used to describe a) the organization responsible for paying the tax and b) the basis used to calculate the tax. In the example above, the State of Texas did not file suit because their hotel tax law clearly states: “A hotel’s owner, operator, or manager must collect hotel taxes from their guests.” While it is easily argued that an OTA does not own, operate or manage lodging facilities, the jury in the San Antonio class action ruled that the OTAs “controlled” the hotel rooms they sold and were therefore responsible for paying occupancy taxes.

The arguments on this issue are likely to be the most aggressively contested. Again, the OTAs may be at a disadvantage if they are trying to convince a jury that they are not technically selling hotel rooms under the merchant model when the travel seller provides customer care and the consumer’s credit card statement reflects the name of the distributor, not the hotel, as the merchant of record.

Assessing sales taxes on organizations located beyond the boundary of the local tax jurisdiction has been an issue since the origin of internet e-commerce. Many US states (rather ineffectively) now ask taxpayers to voluntarily provide the amount purchased over the past year over the internet where local sales taxes were not paid. Tax payers are then assessed an incremental tax liability based on the amount entered on their income tax return. When it comes to self-reporting tax liabilities, the honor system does not inspire honorable behavior among consumers. The same holds true for hotel merchant taxes.

Don’t talk to Strangers

Intermediaries have no direct relationship with the taxation authorities assessing hotel merchant taxes – no address, phone number, account number, etc. Often, travel sellers don’t even know who the authorities are, let alone any details regarding tax remittance deadlines. In many cases, the electronic messages or tax tables provided by the hotels to the OTA’s only provide a summarized tax amount. Even when the specific amounts are itemized, only a category is provided (e.g. state sales tax 3.5%) and there is no further detail provided regarding the tax authority owed merchant tax.

For travel sellers to fully track merchant tax liabilities and efficiently remit payments, substantial industry technical and process enhancements are required. Throughout the hotel distribution chain – global distribution systems, hotel switches, chain central reservation systems, and property management systems universally only hold a single rate for the specific hotel room type and rate plan booked. The tax amounts may or may not be included in the messaging. In the case of a wholesale, net rate transaction, data elements and business logic do not exist to capture a markup amount, retail price or the itemization of distributor hotel merchant taxes.

It should be noted that for many hotel chains and representation firms, the hotel taxes are not managed at all through interactive availability and booking messages. The tax rates are applied independently by the travel seller based on an offline tax table supplied by the property or hotel brand. In many cases, the tax tables may be provided on manually updated excel spreadsheets.

Without creating example use cases, database schemas and message sets for next generation hotel tax calculation & remittance standards, it will be very difficult to integrate OTA, hotel brand, property and local hotel tax management and reporting processes.

Duck and Cover

Hotel chains and properties may be naively relaxing on the sidelines of the merchant tax issue, curiously watching as the OTAs battle the taxation authorities. Perhaps they should be a bit more attentive as they could also be dragged into the muck somewhere down the line…

New York was not the first city to update its occupancy tax law to change the basis to the retail price paid by the consumer. For example, Los Angeles made the change over five years ago – before filing its suit against the OTAs. Many fail to realize that in late 2004, Los Angeles also made a point to advise the local hotel owners that if they were not able to collect from the OTAs, they would be looking to collect the taxes from from the hotels. The hotels do not want any part of such a practice.

Another group is also taking a very low profile on the issue – travel industry executives normally eager to earn big paydays as expert witnesses. With all the nuances and potential contradictions outlined above clouding the core issues, expertise, experience and clarity are sorely needed. For the jurisdictions, finding top quality expert witnesses has not been an easy task. Several individuals with extensive experience with major hotel chains and global distribution systems have declined lucrative offers to serve as expert witnesses for the plaintiffs. The prevailing feeling, shared by many of their travel supplier employers, was that testifying against the OTAs could be detrimental and result in a career limiting outcome.

It is unfortunate that so many groups are choosing to stand on the sidelines, as many from the hotel community and travel industry could potentially help to identify technological or process related solutions to remedy the challenges presented by the hotel merchant tax issue.

The hotel merchant tax vacation may be over for the Online Travel Agencies

See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil

The tax authorities will be creating a nightmare if they try to make hotels accountable for the merchant taxes – similar enhancements to those required by OTAs to access detailed tax information would be required by hotels to receive markup and tax remittance information from the online travel sellers. At the present time, hotels never see the wholesaler’s margin or the retail price charged by an intermediary under merchant model transactions.

Aside from supporting the lobbying efforts of the Interactive Travel Services Association (ITSA), hiring a battery of attorneys and allocating funds to a legal reserve account on their balance sheets, the OTAs have understandably not made any moves to proactively resolve the merchant tax issue. In situations where they have been compelled by courts to pay tax liabilities, the OTAs have complied, but have taken no steps to create enduring processes that facilitate the smooth remittance of merchant taxes to the jurisdictions.

Due to the ongoing litigation, formal discussions and documentation addressing the merchant tax issue are often forbidden by legal counsel to avoid the risk of such documents being subpoenaed and used by the prosecution in future court proceedings. The concern is that planning processes to facilitate the payment of hotel merchant taxes could be construed by the plaintiff’s attorneys as recognition of and willingness to pay the liability. Similarly, documentation of OTA discussions to mitigate risk created by hotel merchant tax litigation could be characterized in court as intent to evade taxation. The litigation makes formal proactive management of the hotel merchant tax issue very difficult for the OTAs – and there is no indication that the litigation will end soon.

Not All OTA’s Are Created Equal

Just as all tax jurisdictions are not requiring payment of hotel merchant taxes, all OTA’s are not consistently named as defendants in the lawsuits.

The Columbus, Georgia suit that prevailed on appeal to the State of Georgia Supreme Court only named Expedia as the defendant, but the city also has suits pending with Orbitz and Travelocity. For some reason, it does not appear that Priceline has specifically been named in any suits brought by the City of Columbus.

The Washington State consumer class action ignored all the other OTAs and only applied to Expedia. The suit brought by the State of Florida names Expedia and Orbitz, but excludes Travelocity and Priceline – even though the two groups sell hotels in Florida under the same merchant model processes and have typically been named in other hotel tax related suits brought by other jurisdictions.

Finally, Maupintour seems to be the only traditional tour operator that has been named in the various court cases – included in suits ranging from California to Texas and Florida. At this point, it appears that the legal counsels are defining the scope of the suits – perhaps having access to more compelling evidence regarding certain defendants. In some cases where a legal firm has represented multiple destinations as clients, it appears that a common group of defendants are being named. It appears that past success against specific OTA defendants could may streamline the discovery processes based on experience in previous cases.

OTAs Are Not Evil

While hotels clearly would enjoy having all consumer bookings transact directly to capture the full margin for themselves, all realize that they are not able to efficiently or cost-effectively aggregate the expansive hotel demand captured by the OTAs. Years of multi-channel ad spending have made the Priceline Negotiator, Travelocity Gnome, and Expedia’s Yellow Suitcase readily identifiable by mainstream travelers.

The OTAs are monetizing that awareness and website traffic by demanding significant discounts in return from the hotel suppliers. Hotels now represent the largest margin source for the online travel companies. OTAs love the hotel industry – it is highly fragmented on an ownership, management and marketing level. Additionally, many travel industry industry distribution practices have commoditized a product that, by nature, should be highly differentiated. While the OTAs have contributed to the commoditization effort (the “Four-star Hotels at Two-star Prices” concept does not make any hotel owner very comfortable,) they are now better positioned – especially with hotel review sites like Expedia owned TripAdvisor, to help the hotels differentiate themselves across a large audience.

A recent Cornell Center for Hospitality Research study documented the beneficial “billboard effect” gained by hotels participating in OTA programs. Travelers frequently use the OTA to search and comparison shop, but may elect to book out of channel directly with the hotel or through a different intermediary. For most hotels, working with OTAs makes good business sense as long as the relationship remains a partnership and avoids one-sided win-lose negotiation scenarios.

High Stakes

The amounts in play with hotel merchant tax settlements are not trivial. Merchant model transactions represent the vast majority of OTA hotel bookings and that those hotel bookings are now beginning to represent a majority of an OTA’s margin contribution. For Expedia, in the 3rd Quarter of 2009, merchant model bookings encompassed 77% of hotel revenues and hotel revenues were 64% of total company revenues. This means merchant model hotel bookings impact 49% of Expedia’s revenues.

A selection of recent unfavorable awards against the OTAs have included:

- Anaheim – $21 million

- San Antonio (and 170+ Texas cities) – $20.6 million

- San Francisco – $30+ million

- Washington State consumer class action – $19 to $134 million (Expedia only)

Top Hotel Lawyer Jim Butler of Jeffer Mangels Butler & Marmaro writes in his Hotel Law Blog that based on present awards and assessments made, there is more than $300 million at stake… and that was before the State of Florida and the five Florida counties joined the scrum that now exceeds 200 municipalities.

The risk is greatest for Expedia and its Hotels.com and Hotwire.com brands. In the San Antonio decision, Expedia was targeted for 73% of the award; in the Anaheim case, Expedia’s liability exceeded 83% of the award. In response to the negative court outcomes, Expedia allocated $74 million for legal reserves in the second quarter of 2009 to address hotel merchant tax suits for its Expedia, Hotels.com and Hotwire business units.

A good example of the scope is provided by Priceline estimating that it has generated $800 million in gross profit from merchant hotel transactions since its inception for hotels located in over 1,000 jurisdictions with aggregate tax rates ranging from 6% to 18%. That is not only a large number looking backward, but a considerable source of margin moving forward.

A Silver Tax Bullet for Cities?

US Cities are desperately trying to balance budgets – cutting costs and maximizing revenues in every conceivable way. With the economic downturn reducing tax revenues, even though many hotel merchant tax cases were initiated more than five years ago, the timing of the merchant hotel tax court decisions is garnering attention from city officials.

For many elected officials, targeting the OTAs for hotel merchant taxes represents an ideal method to increase tax revenues:

- It does not increase the tax burden on the voters that comprise an elected official’s constituency

- It does not increase the tax liability of the traveler or deter organizations from meeting in the city

- It does not increase the tax liability of the hotel operators

Assuming a conservative 10% hotel tax rate and 15% merchant discount percentage, hotel merchant tax liability would potentially represent 1.5% of aggregate hotel revenues. At a more typical 15% tax rate and 25% discount, the amount jumps to 3.75% of revenues. These are huge numbers for the revenue starved locales.

For destinations that had tax laws clearly stating that hotel taxes were paid on the amounts collected by the hotels, laws are being updated to change the basis to the amount paid by the consumer. This creates a new, incremental revenue stream for the jurisdiction. Looking forward is not the only alternative – Many of these suits seek damages for unpaid hotel merchant taxes dating back over several years. Depending on the statute of limitations, back taxes can quickly multiply the size of a one time payday. As an added bonus, if a court can be convinced to include punitive damages, penalties and interest, the amount awarded to the locale can increase substantially.

Be Careful What You Wish For…

When the first hotel merchant tax cases were initially filed in the early ’00’s, the cities recognized that genial discussions with the OTAs on the subject would prove fruitless. In an effort to minimize court costs and rapidly capture the contested tax monies, the cities unsuccessfully attempted to fast-track the process. This approach did not sit well with the courts and many cases were dismissed, not on their merits, but based on the locale’s failure to exhaust all available administrative remedies before filing the lawsuit. The early hotel merchant tax pioneers had to regroup – some gave up, but others chose to move forward by performing expensive and time consuming tax revenue audits.

Columbus, Georgia was one of the first communities to win a court victory. It was not an easy task, the case reportedly required over 80 depositions and the filing of thousands of documents. This was only the beginning of the story. Appealed to the Georgia Supreme Court, the City of Columbus was again victorious. On the surface, a landmark victory, but there was also a downside.

Expedia delisted the City of Columbus in August 2008. In a study conducted by compiled by two Columbus State University professors at the D. Abbott Turner School of Business, it was estimated that the Columbus economy lost $9.3 million in revenue and $1.4 million in taxes for the 12 months ending June 2009 as a result of this action. In contrast, a recent HotelNewsNow article indicated that its removal from Expedia was not hurting Columbus as badly as some may think – primarily due to its relativly strong corporate business demand as opposed to the more leisure oriented business typically provided by the OTAs.

It does appear a bit malicious for the OTAs to punish the small jurisdictions by cutting them off; especially as this has not been the case in larger destinations like Anaheim, New York City, San Francisco and San Antonio. Obviously, a more practical solution would be to negotiate retail agreements with the impacted properties for standalone hotel bookings. The commission rate could easily be equated to match the wholesale discount under the merchant model. Unfortunately, with the matter being decided in the courts, like in many divorces, reasonable action often takes a back seat to winning – or inflicting the greatest pain in the process.

Of course, to make the situation even more convoluted, the City of Columbus is now seeking an injunction to require Expedia to re-list all Columbus hotels on its website. The city is now contending that searches for Columbus, Georgia are being fulfilled with hotels in neighboring Phenix City. The city will reportedly seek damages for lost revenues for the duration of the delisting. Columbus’ legal counsel has also raised the prospect of filing suits against other OTAs that have also stopped listing Columbus properties.

Hotel Limo Chasers?

The huge amounts being contested across a large number of destinations are not only capturing the attention of the tax authorities. Legal firms working on a contingency basis are soliciting municipalities, counties and states, recommending that they also file suit to get their fair share of the hotel merchant tax pie.

Duane Marsteller, reporter for The Bradenton Herald quoted Manatee County Commissioners Donna Hayes and Larry Bustle as saying the county’s agreement with Tallahassee law firm Nabors, Giblin & Nickerson, attorneys’ fees are capped at 30% of any amounts recovered. The arrangement was confirmed by NGN law partner Ed Dion, “If we don’t recover anything, there’s no expense to the county.”

Due to these contingency arrangements, there is limited risk to the tax jurisdiction if the case is lost. Ray Williams, Manatee County’s director of delinquent collections reportedly declined at least five other law firms’ pitches to sue on its behalf before the County commissioners voted to pursue the suit.

Can one fault the lawyers? They are capitalizing on an opportunity to assist financially challenged municipalities capture higher tax revenues… OK, that perspective may be a bit too altruistic – this represents big money for the lawyers, as well as the communities.

If precedents begins to favor the destinations, the risk of taking similar cases on contingency is reduced. It should also be noted that by undertaking class action work, law firms working on a contingency basis can maximize their earnings by expanding the number of jurisdictions represented (and the corresponding award) while minimizing the number of cases being tried – a highly effective method to increase profits to the legal firm.

The peasants are revolting. Instead of taking to the streets, local municipalities are taking to the courtrooms.

Follow the Leader

Combining the ability to grow tax revenues without alienating local constituents and the limited risk associated due to contingency arrangements with legal counsel, the conditions appear to be ripe for growth in the number of hotel merchant tax cases against the OTAs.

Unfortunately for the OTA’s, with thousands of tax jurisdictions in the US, each with its own particularly unique description of its hotel tax code, it is realistically impossible to determine where a perceived tax liability may exist. A more urgent question may be where the next merchant tax suit will originate. Many states, cities and counties, now emboldened by victories in other parts of the country, are lining up to see if they too can score a big payout.

The nearly simultaneous filings by the State of Florida and six Florida counties closely followed the OTA class action loss in Texas. Houston was not a party to the Texas class action suit, but is now reportedly pursuing its own suit. Following initial successes in Anaheim and San Francisco, thirty-seven California municipalities have now initiated hotel tax audit procedures.

The scope of the litigation is staggering. Priceline, in its 3rd Quarter 2009 10-Q filing with the US Securities & Exchange Commission lists the following active class action suits:

- City of Los Angeles v. Hotels.com, Inc., et al.

- City of Rome, Georgia, et al. v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- City of San Antonio, Texas v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- Lake County Convention and Visitors Bureau, Inc. and Marshall County, Indiana v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- Louisville/Jefferson County Metro Government v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- County of Nassau, New York v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Gallup, New Mexico v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- City of Jacksonville v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- The City of Goodlettsville, Tennessee, et al. v. priceline.com Incorporated, et al.

- The Township of Lyndhurst, New Jersey v. priceline.com Incorporated, et al.

- County of Monroe, Florida v. Priceline.com, Inc. et al.

- County of Genesee, MI et al. v. Hotels.com L.P. et al.

- Pine Bluff Advertising and Promotion Commission, Jefferson County, AR, et al. v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- County of Lawrence v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

Additionally, Priceline listed the following actions filed on behalf of individual Cities and Counties:

- City of Findlay, Ohio v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- City of Chicago, Illinois v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- City of San Diego, California v. Hotels.com L.P., et al.

- City of Atlanta, Georgia v. Hotels.com L.P., et al.

- City of Charleston, South Carolina v. Hotels.com, et al.

- Town of Mount Pleasant, South Carolina v. Hotels.com, et al.

- City of Columbus, Ohio et al. v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- City of North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- Wake County v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Branson v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- Dare County v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- Buncombe County v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- Horry County, et al. v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Houston, Texas v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Oakland, California v. Hotels.com, L.P., et al.

- Mecklenburg County v. Hotels.com, LP, et al.

- City of Baltimore, Maryland v. Priceline.com Inc., et al.

- City Comms of Worchester, Maryland v. Priceline.com Inc., et al.

- City of Bowling Green, KY v. Hotels.com L.P., et al.

- Village of Rosemont, Illinois v. Priceline.com, Inc., et al.

- Palm Beach County, Florida v. Priceline.com, Inc., et al.

- Brevard County, Florida v. Priceline.com, Inc., et al

Priceline also adds this ominous warning for investors, “Additional state and local jurisdictions are likely to assert that the Company is subject to, among other things, hotel occupancy and other taxes…”

Retreat?

Anyone serving in an executive role at an OTA would not be working there if the word “retreat” was part of their vocabulary. OTAs tend to excel in conventional warfare – declaring their objective, loading up their ammunition and attacking until the enemy is eradicated or resources are depleted.

However, some OTAs have acquired European hotel booking sites that are thriving using the retail/commission model. Priceline’s Booking.com and Expedia’s Venere.com may provide a safety net for both firms if the US merchant tax litigation landscape gets any more crowded or hostile.

An overlooked fact is that Hotels.com has used the retail/commission model successfully for years, typically for independent hotels and smaller destinations where booking volume does not justify the ongoing management of net rates by both parties. Retail hotel transactions currently comprise a small portion of Hotels.com’s total sales volume.

The recent economic downturn has enabled the OTAs to renegotiate hotel merchant agreements with hotel companies on more lucrative terms. By negotiating deeper hotel discounts and last room availability conditions, despite their undeniable preference to maximize margins, the OTAs may ultimately end up being better positioned financially to sustain the merchant model and absorb hotel merchant tax liabilities.

Making Room at the Trough

One final perspective that makes this issue even more ludicrous is how the room occupancy taxes that are being collected are spent by the local communities.

The same budget challenges that have helped elevate attention to hotel merchant taxes as a potential revenue source have also put the base hotel room taxes at risk for allocation away from the tourism related uses as originally intended. The issue has become significant enough for International Society of Hotel Association Executives (ISHAE) to form a Council on Room Tax Solutions to investigate the problem.

The ISHAE’s Room Tax Solutions Council has identified three specific issues that require attention:

- Room tax rates are increasing

- Room tax revenue intended to support tourism, is being reallocated for other purposes

- Governments are increasing room taxes to fund general budget items

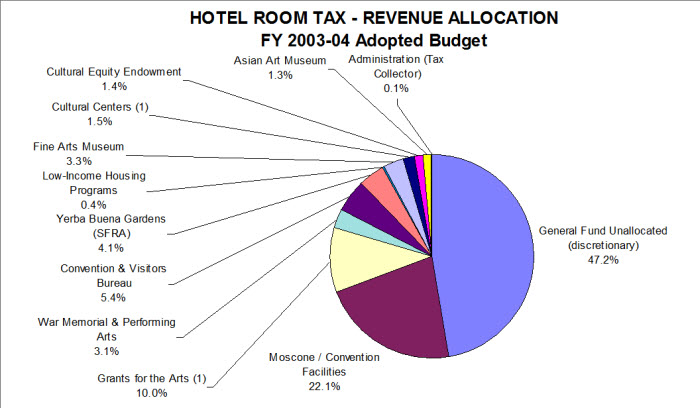

In many communities, hotel room taxes spread the wealth through support for a variety of specific and non-specific public services. The pie chart above shows nearly one-half of San Francisco's falling to the city's general fund.

In many cases, for example, the State of Texas, statutes require that revenue from the hotel transient occupancy tax may be used only to promote tourism and the convention / hotel industries. In other jurisdictions, portions of the taxes collected may be placed into general administrative funds to support other civic programs.

As most hotel taxes are levied on a local level, there reportedly are ample opportunities for hotel tax revenues earmarked for tourism to be committed to “fringe” tourism initiatives, including road construction, parks or drainage projects. While it can be argued that such projects support tourism by maintaining local infrastructure, with average US room tax rate was 12.62%, there are concerns that excessive hotel tax rates can inhibit tourism and negatively impact hospitality industry employment and profitability.

Finally, Some Good News for the OTAs

Earlier this morning, Tom Botts on the Hudson Crossing blog revealed a decision by the US court of Appeals in the Louisville/Jefferson County Metro Government v. Hotels.com case. A win by the OTAs!

The decision was justified as Louisville’s hotel tax law established the basis as the entities doing business as hotels, not the occupants of the rooms – this correctly negated the ability of the Louisville to tax the retail price of the room as opposed to the wholesale price. The court cited the Georgia Supreme Court decision regarding the City of Columbus, where the tax basis was “the charge to the public.”

The court also clearly communicated that the OTAs do not physically make the rooms available to the guests, again a clear and appropriate conclusion. Finally, the court reasoned that any loopholes that exist providing a financial tax advantage to an OTA over a hotel operator should be addressed through legislation.

This case should establish two significant standards – First, a supporting precedent for the Georgia decision regarding the basis for hotel merchant taxes. Hotel merchant taxes should apply only if the tax law uses the price paid by the consumer as the basis for the tax. Second, it clearly suggests that closing the loophole providing favorable tax treatment for OTAs on merchant hotel transactions by changing existing tax laws is a simple legislative process. One can anticipate more jurisdictions that have not filed suits to follow the lead of New York and others to start proposing changes to enable the collection of hotel merchant taxes.

More Breaking News: OTAs sue New York City

Not to be scooped by Tom Botts, Dennis Schaal of Tnooz reports that the OTAs, this time, supported not only by ITSA, but also the American Society of Travel Agents (ASTA) and the United States Tour Operators Association (USTOA) are suing New York City in New York State Supreme Court over the update to the hotel occupancy tax law.

As presented above, the New York law improperly attempts to assess merchant tax based on an incalculable retail hotel rate for package bookings, but the suit also questions if New York City even has the authority to assess taxes as opposed to New York State. With both ASTA and USTOA entering the fray, hotel merchant tax has now officially expanded beyond the realm of OTAs and hotels to become a legitimate travel industry concern.

If I Ruled the Hotel Merchant Tax World

To be clear, it is fairly certain I would never be appointed to the position of national hotel room tax Czar – my platform would definitely alienate almost every constituency that has weighed in on this topic. Also, it seems that logic and politics parted company many years ago, but us idealists can still dream – and the US Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals has definitely aided the cause…

So here is the RockCheetah Hotel Merchant Tax Manifesto:

- Hotel Occupancy Taxes should be calculated based on the retail price paid by the consumer for accommodation.

- Hotel Merchant Tax applies solely to stand-alone hotel bookings.

- Packages (including other material components sold simultaneously in a bundled transaction) are exempt from Hotel Merchant Tax.

- For package bookings, the basis for the hotel occupancy tax should be the revenue received by the hotel.

- Itemized service fees listed by OTAs independently from the hotel component shall not be subject to Hotel Merchant Tax.

- When tiered distribution scenarios including multiple intermediaries arise, each distributor shall be independently responsible for its own Hotel Merchant Tax liability.

- Hotels should be required to provide travel distributors with Hotel Merchant Tax calculation details in a standardized structured format including itemized information regarding tax authority, revenue basis applied, calculation methodology, tax rates and applicable date ranges.

- A centralized repository of hotel room tax amounts and rules should be established for the shared benefit of hotels, local municipalities and travel sellers. This repository should include reference information regarding tax laws, jurisdictional boundaries, remittance policies, etc. Functionality enabling status management, FAQ’s and update notifications for all relevant parties should also be incorporated.

- To facilitate enhanced Hotel Merchant Tax messaging and repository functionality, a Uniform Global Identifier should be established for each hotel location, tax jurisdiction and travel seller. This identifier can serve as the mechanism to clearly identify booking sources and destinations.

- A neutral non-profit entity should oversee the governance of the repository and coordinate policies across all major hotel related membership associations.

- Jurisdictions, distributors and hotels should be independently responsible any audit processes based on the structured data standards and processes defined.

Yes, the Open Travel Alliance hotel industry database schema and messaging would require updating. System upgrades would also be necessary to enable automated audit trail and transaction bread-crumbing functionality. However, by maintaining a distributed processing methodology, significant interfacing or centralized processing requirements can be largely avoided.

Cost is also a legitimate concern, but given the large number of hotels, travel sellers and tax jurisdictions, repository management costs can be kept very low on a unit basis by spreading financial responsibility across the user groups. It is easily argued that the cost of developing and deploying a central repository to serve as an information clearing house would be substantially lower than doing nothing. Having hotels, tax authorities and travel sellers attempt to implement Merchant Tax calculation, assessment, collection and remittance processes using non-standardized and proprietary tools would create unfathomable inefficiencies, increasing costs for all involved.

Hotel Merchant Taxes are a new and logical result of changing hotel distribution and pricing models. If properly implemented and administered, these taxes can provide much needed tourism funding to local municipalities and eliminate the current tax liability inequities between hotels and travel sellers. By adopting a process that allows each entity to maintain independent responsibility for its own pricing and tax management strategies, open market forces will reward those organizations that are able to create the greatest value through the most efficient means. The end result should yield increased tourism with less friction for travelers, travel distributors, hotels and cities.

I would hope all groups involved could come together, reach common ground and work together to provide a viable solution to a current challenge that can only be described as a quagmire. Fighting in the muck will only exhaust the participants and require the expenditure of energy and resources that could be more productively allocated elsewhere. The industry needs to take a proactive approach to rise out of this precarious swamp.

The approach above creates a potential win-win-win situation. The only losers would be the legal firms currently profiting from the iterative process of seeing all permutations of jurisdictions and travel sellers work through the issues in court. If you made it through this lengthy post, please leave a comment. If you agree, disagree, recommend changes or can propose a more equitable solution, your input would be most welcome. Both the hotel industry and the OTAs need this issue to disappear.